Bianca Tschaikner 2018

map of all the Riu d’art artworks

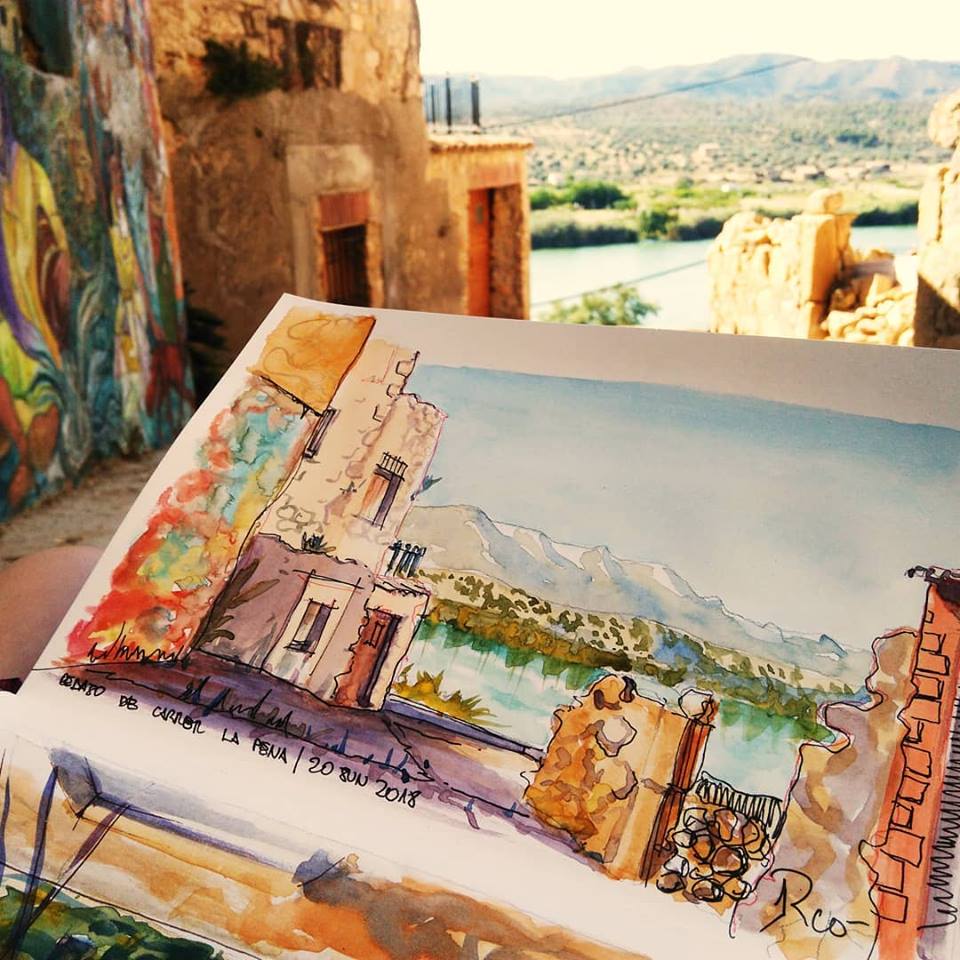

‘Fillas de la Riba’

This artwork is part of ‘Fillas de la Riba’, a series of monochrome murals on old wooden doors spread through the old streets around Riba-roja d’Ebre, created by the Austrian artist Bianca Tschaikner. It’s a playful reflection on Riba-roja’s past, inspired by old photographs of the inhabitants of Riba-roja traditional clothes, ancient juniper production, the river Ebre and stories from the remarkable life of Teresa Aguilà Garcia, an illustrious inhabitant of Riba-roja.

Filla de la Riba, daughter of river, gave name to the art project in which I worked here at the Riu d’art Residency in Riba-roja d’Ebre, Catalonia. She was inspired by old photographs villagers over the last century.

Filla de la Riba, daughter of river, gave name to the art project in which I worked here at the Riu d’art Residency in Riba-roja d’Ebre, Catalonia. She was inspired by old photographs villagers over the last century.

Her new book, SAVARI – an illustrated journey through Iran and India has been published in Austria Bucher Verlag and is available here.

Fillas de la Riba Daughters of the River

Fillas de la Riba is a network of monochrome wallpaintings on old wooden doors spread about the old town and surrounding streets in Riba Roja d’Ebre, a small rural village in Catalonia, Spain. It’s a playful reflection on Riba-Roja’s past, inspired by old photographs of Riba residents in traditional clothes, ancient juniper production, the river Ebre and stories from the remarkable life of Teresa Aguilà Garcia, an illustrious resident of Riba-Roja.

Riba de Ginebre | Juniper River

This door is inspired by the juniper ovens. Some years ago a group around Josep Aguilà, following the reports of very old people, rediscovered seventeen juniper ovens around the village, dome shaped stone-ovens where people used to make juniper oil.

Filla de la Riba

Filla de la Riba, daughter of the River, gave name to the art project I was working on here at Riu’d Art Residency in Riba-roja d‘Ebre, Catalonia.

She was inspired by old photographs of village residents from the beginning of the last century.

La Sirena | Stories from the River

The village of Riba-roja d’Ebre is situated in a loop of the river Ebre, and before there were trains, people used boats to transport goods.

The first story I heard about the river was from a man named Paquito who told me that once there was a man who shipwrecked, couldn’t not swim and saved himself by holding onto a ram’s tail.

Josep Aguilà in turn told me that until the 1920, hundreds of ships would pass the village every day. Some villages next to the river even charged tolls. Downwards the ships would swim with the stream, and upwards with sails or with the help of horses or mules who would pull the ship with a rope from the shore, helped by men with oars inside the boats.

In these days, as there was no running water, women had to go to wash at the river, amongst them Teresa Aguilà. Ships would pass by, and the boat men on the ships would give them compliments, some more elegant than others.

Sometimes words with double senses were exchanged between the boat men and the laundresses. The men would ask them about the state of wetness, pretending to mean the river but meaning something else, and the women would ask whether it was hard and long, pretending to mean the oar but actually meaning something else…

Roses for Rosita

During my stay at Riba-roja d’Ebre, of course I soon had noticed and admired the hundreds of beautiful pot plants that were placed in every corner of the village. Riba-roja is, like many spanish villages, in a severe state of decay that is less romantic than saddening. Especially the beautiful old town of Riba-roja was really desolate, with crumbled walls and ruins where once beautiful houses had been.

The pot plants, lush and green, were decorativley placed in door cases, walls and along the narrow streets and conveyed the comforting feeling that old Riba-roja had not yet been left to its fate. It showed that there still existed some love and care for this old place. It seemed a bit like fairy magic.

There was definitely a good spirit at work, and on the last day before the presentation of the artworks I got to meet the good spirit. She entered the bar where we would have lunch and gifted us with some of her handmade tote bags, just like that. I had never seen her before.

Her name was Rosita, and she told me that after her husband had died she had gone to the mayor and suggested him that if he would pay for it she would decorate the village with pot plants and take care of them. And so she did.

And so I painted some pot plants for Rosita.

Teresa and the wolf

This door painting is about Teresa Aguilà, grandmother of Josep Aguilà, who told me many stories about her during my stay at Riba-roja d’Ebre.

This is the story of Teresa and the wolf as told by Josep.

Teresa Aguilà was born in Riba-roja d’Ebre in the year 1895 and she lived to be 105.

When she was seven, both of her parents died within a week and she went to stay with an aunt who was very poor. So little Teresa, at the age of seven, had to begin to work as an employee in the house of rich people. She worked throughout her childhood and youth, for which she did not even get any payment, only food. She washed clothes, cleaned houses, worked on the field and in the kitchen. Of course, she did not have time to school. But when she was fourteen, she decided to pay a tutor to visit her for an hour every night and teach her how to read, to write and basic mathematics. Teresa read the newspaper every day up to the age of 103, even picked it up herself, at the age of 104 she still looked at the photos and the headlines.

And here comes the incredible story of Teresa and the wolf: When Teresa was 12 or 13, she worked at a finca, a farm three hours away from the village. Every week she had to go and get food for the workers from the village, alone, only accompanied by two mules. She was woken up at 3 in the night, and at 4 her journey began. One night, on her way from the farm to the village, she noticed that there were wolves behind her, coming closer and closer. Terribly scared, she thought how she could save herself. Finally, she took a long rope, tied one end to the saddle and let the other end fall to the ground, and moving the rope she stirred up dust, which frightended the wolves, and they dissappeared.

When she would arrive in the village, the people who prepared the food would force her to attend mass. They would not give her anything to eat, neither before nor after mass. To check whether she actually had attended mass, they used to ask her which priest was holding the mass and what the color of his robe was.

But Teresa, who was as starving as smart, would go to the church, check out the priest and his robe and then go straight back to the house, where she sneaked into the hen house and stole two or three freshly laid eggs, which she ate raw. On the way back, when she was out of sight of the village, she stopped the mules and took a bit of bread and sausage and finally had something proper to eat.

Teresa and the hunger

When Teresa Aguilà was 17 years old, one of the extra works she did was something called “espigolar”. Around her village there were many olive fincas, and “espigolar” meant to go to the owner after the harvest was done and ask for permission to pick the last few overlooked olives.

It meant looking for olives on the fields after there were practically none left, there were so little olives left that it was not worth the work, almost absurd to do it, and only very poor people would do it.

At night, after a hard day of work, Teresa and her friend Rosita, would go to “espigolar” to a finca where they had gotten permission to do so. After two or three days of work they collected a ridiculously little amount of olives. But then they realized that on the way to the finca there were some fincas where the olives had not been harvested yet, and every day when they would pass by they would pick two, three kilos from those trees without permission, which was much more than they could ever had picked doing “espigolar”.

They sold these stolen olives and then Teresa said to her friend: What do you think of buying a tupi (a ceramic pot) with the money? So every day we could buy some beans or chickpeas and prepare some nice food.

This is, in the words of Josep Aguilà, who told me this story, the spirit of survival. Had they been caught, they would have been physically punished or would have ended up in prison.

This gives you an idea of the bitter poverty Teresa suffered from. But it was even worse. After I told the story to the other artists of the residency, the organizers of the residency told me that when they told Josep about some found some strange looking rodent they had found on their olive farm, Josep would say: My grandmother used to eat that!

Teresa and the dictator

This is the last and the certainly the most haunting story of the life of Teresa Aguilà. As you already know, Teresa had to fight many wolves in her life, but the biggest one was Francisco Franco, the Spanish dictator, and the regime he embodied.

Here is the story as it was told to me by Josep Aguilà, the grandson of Teresa.

Teresa, who was called Tereseta by her friends, or even Teresó (a male sounding version of her name), lived in a time where women faced even more discrimination than today. 90 years ago in Spain, women were mostly locked up in their houses and were not really able to connect with people or surroundings outside their families.

As you already know, Teresa was very poor and could not go to University, but she was very aware and critical of the power the rich people and the ways they abused poor people, especially women. Women not only earnt less than men, often they did not get any money for work at all and were frequently sexually abused.

Teresa herself had to work with an army captain in Reus, the next bigger city, as a maid and taking care of the child you see in the picture. She also had to work in different villages helping in the olive and hazelnut harvest, and sometimes she visited her brother in Barcelona working with him in the coal mines in Figol near the Pyrenees.

So she would often get out of her village, and she would adquire her knowledge not at the university but on her trips. This also added to the fact that Teresa was more open-minded than the other women in her village. She also liked to talk with men about everything around the work on the fields, she knew all the works perfectly well, the seedtimes, the influences of the moon, and she knew everything about plants and trees – in short, she knew things that the average woman did not know, who would only help on the fields but would not be interested in her work further.

Teresa also loved talking about politics with men during reunions that took place mostly between 1930-36 and of which many were secret, because these reunions were prohibited. She was lucky to have a husband who trusted her and did not harass her for meeting other men at these reunions. After the reunions, Teresa would go and explain everything to the women of the village, visiting each of them individually in their own house.

Many people would later tell Josep that Teresa was ahead her time. She had a very open mind, was feminist and leftist, without being extreme.

On the 14th of april, 1933, a clock was put in the clocktower of the church from the Republic (the Republicans was the democratically elected spanish government that later would be overturned by the later dictator Francisco Franco by a coup d’etat), and Teresa and a group of other women participated in the celebration. There is even a photograph Josep showed me from that day with Teresa carrying a republican flag.

The Spanish civil war (or rather the Spanish “uncivil” war, as Josep calls it) ended in 1939. Many Republicans were imprisoned and executed, and many others fled either to other countries or places inside of Spain where nobody would know them to avoid persecution from the Franquistas. Teresa moved to Barcelona with her husband and daughter, where she would work in a farm house of a Franquist owner who did not care about their political views. Then, in 1940 Teresa decided to visit her village for some days, against all advice of family and friends who had come together at a family reunion to discuss the matter. On the way to Riba-roja with her daughter, she met some people from her village who warned her to go to the village and told her to return immediately, because it was too dangerous. But Teresa told them that she had no reason to be afraid because she did not collaborated in the death of anybody, on the contrary, she had even defended saved a Franquists from execution and therefor certainly nobody would harm her.

The man she had saved had been a widower with two daugthers and the Republians were planing to execute him and Teresa, who had been an orphan herself, convinced them that it was a great injustice to turn these two little girls into orphans. Thanks to Teresa, the man was set free.

On the second day in her village, she was arrested, following a triple denunciation. Three “brave” men seized her at her house, beat her up and kicked her, threw stones at her, spat at her and shaved her head. It was so horrible that the memory of the incident makes Joseps mother-in-law with her 96 years still trembling with terror.

They put her in the local prison (a building which still exists today and still looks like a prison, but is not used anymore) held a propaganda trial and accused her of “helping the rebellion”, ignoring the fact that the rebell had been Franco, and Teresa had never carried a weapon or harmed anybody. She was sentenced to 15 years of prison just because she had carried the Republican flag in 1933 and because she had been heard speaking about politics.

Of these 15 years she spent four and a half years in prison in Barcelona, in a prison that once had been a convent and which now is a shopping center. What happened to Teresa happened to thousands of Republican women – 40.000 women went through that prison and now only a small plaquette (two millimeters of memory for each of them, says Josep) reminds of these women who’s only crime it was to be Republican.

Inside the prison, Teresa secretly made herself a ring from some silver coins her daughter, who walked many days to see her in prison, brought her, engraved with the initials of her husband, J.A. for Josep Alabart (which now happen to be the initials of Josep Aguilà) and herself, T.A. for Teresa Aguilà.

In the prison, they tried to brainwash them, telling them that they were demons, that the civil war had been their fault, and that they were useless and unwanted by everybody outside and that the world continued better without them. Many were raped by men as well as by women, which the prisoners were pressured to tolerate without resistance in order to get some benefits like more food or more free time.

Thanks to her ingeniuity, Teresa managed to push herself through prison. But when she came out of prison, she was a different woman. Four and a half years of prison had changed this woman who had been so alive, so happy, so talkative, so intelligent. The woman who returned from prison was scared and dumb and almost speechless, although judging from the photos I saw of her at old age she seemed to have gotten her old self back after time. What had happened during these four years of prison that a person like Teresa would come out of it so scared?

When Teresa’s husband learnt that they had imprisoned his wife, he did not understand, repeating “this is not possible, she was such a good woman, she didn’t harm anybody…” He was so shocked about the unbelievable and went crazy over the loss that he had to stay at a psychiatry for some months. When he was well again, he went back to work on the farm near Barcelona.

Teresa and her daughter, Josep’s mother, would later educate him “badly”, as Franquist, in order to protect him (the Franco regime would continue until 1977). But then again, they educated him well enough that he began to see how things were by himself, and then they talked openly and in detail to him about everything.

I met Josep Aguilà on my first three days of Riu d’Art artist residency, a lively, quick-witted and warm-hearted man overflowing with knowledge and a contagious enthusiasm for many issues. This remarkable man owning so much brain, heart and wit in retrospective gives me an idea of how the personality of his grandmother Teresa might have been.

During the daytime he, together with the organizors of the residency, would lead us around the hills surrounding the village, the dam, the hermitage and one of the juniper ovens he had discovered, answered all of our questions and generously sharing his abundant knowledge with us.

During the night, he invited us artists to his “Bar Josep”, which would consist of a huge table dragged out on the street in front of his house, where he would serve us delicious craft beer and cheese and good, fun conversation.

When I told him that I wanted to hear all the stories of the village, he told me the story of his grandmother and the wolf. Then he had to travel back to Barcelona, but during my whole stay in the village he kept emailing me stories of his grandmother and stories from the village.

Yesterday he wrote me a mail where he explained the story of Teresa and the civil war, which he had told me before, in more detail. So now I can share it with you.

Thank you Josep for sharing these deeply moving stories of Teresa with me and for giving first context and then sense to my artistic stay and work in Riba-roja, where I tried to create some humble memorial for Teresa, knowing that tens of thousands of door paintings would not be enough to adequately remind of and honor Teresa and the other brave Republican Catalan women who were attacked, wounded and killed fighting the horrible beasts of Franco. Hopefully one day these women will get the memorial they deserve.